A Modest Proposal: How to cut the cost of extending #ARP subsidies by several billion dollars

I haven't written about the ACA's Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) rule in awhile. I was pretty obsessed with it a few years ago, and I still check in on it from time to time, but otherwise I've mostly moved on to other things.

HOWEVER, the MLR rule is still pretty important...and while the dollar amounts I'm about to discuss aren't much more than a rounding error in terms of federal budget numbers, it's possible that the could play a small role in helping get a much larger project moving forward.

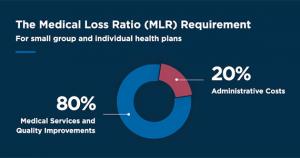

Before I begin, here's a short refresher on how the MLR rule works:

- Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance carriers are required to spend at least 80 - 85% of their premium revenue on actual medical claims (80% for the Individual and Small Group markets; 85% for the Large Group Market). In this post I'm looking only at the Individual market.

- If a carrier spends less than 80% on claims in a given year, the difference must be rebated to the policyholders, on a 3-year rolling average.

- This has resulted in billions of dollars being paid out to millions of ACA enrollees and/or business owners over the past decade.

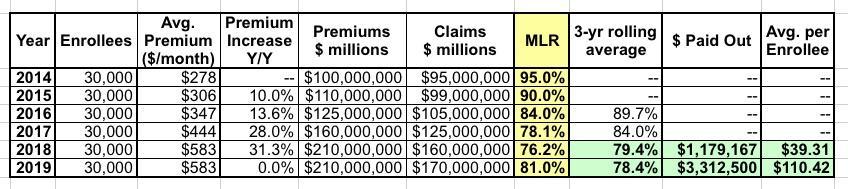

Here's how the 3-year rolling average works. Let's say an insurance carrier has exactly 30,000 enrollees each year. Their average unsubsidized premiums started at $278/month in 2014 and increased by 10% in 2015, 14% in 2016, 28% in 2017, 31% in 2018 and then stayed flat for 2019.

Their MLR was way too high the first two years...in fact, they lost money in 2014 and probably in 2015 as well, since administrative overhead/etc. costs more than 5%. Things started to stabilize in 2016, and in 2017 they actually overshot the mark slightly. In 2018 they seriously overpriced, so they instituted a price freeze in 2019 to try and comply with the ACA's 80% MLR rule.

The three-year average for 2014-2016 is nearly 90%, and for 2015-2017 it was still 84%, so they didn't have to pay back any rebates. For 2016-2018, however, they fell slightly below 80% to 79.4%, so they had to cut small checks, averaging around $40 apiece, to their enrollees. In 2020, they sent out larger rebate checks for around $110 apiece to each of their enrollees, since their 3-yr average MLR fell another point to 78.4%.

OK, so that's MLR 101. There's a bunch of other caveats & modifiers involved, but this covers the essence of it.

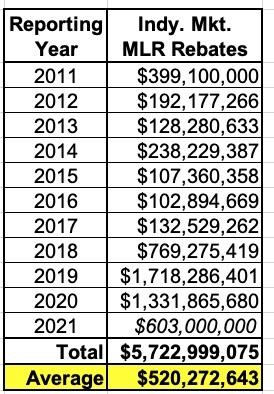

So how much rebate money are we actually talking about here? Well, here's a summary of how much has been paid out to individual market ACA policyholders since the program started (the 2021 figure is an estimate; these payments will go out sometime in August/September of 2022):

Over 11 years, individual market MLR rebates have averaged over a half a billion dollars per year...and over $1.1 billion per year for the past four years.

While I applaud the ACA's Medical Loss Ratio Rebate provision overall, there's one important flaw in how it works, which I originally addressed two and a half years ago: Due to an oversight in the wording of the section of the ACA devoted to laying out MLR rebates, some subsidized individual market enrollees are actually PROFITING off the program.

The reason why is pretty simple: The individual market MLR rebate payments are sent, in full, to the policyholder regardless of whether or not their premiums are being subsidized by the federal government or not.

Let's suppose you earn $100,000/year (too much to qualify for ACA subsidies) and enroll in the Silver benchmark policy which has full-price premiums of $600/month ($7,200/year). Your carrier came in with a 3-year rolling average MLR of 79%, so they have to pay 1% of the premiums back, which means you'd receive a check for $72.

Hey, nice! Not a lot of money, but hey, $72 is $72.

Now let's say you enroll in the same policy, but you only earn $30,000 (240% FPL). Under the original ACA subsidy formula, you'd have to pay around 8% of your income for the benchmark plan, or $2,400 for the year, with the other $4,800 covered by federal APTC assistance. Under the enhanced ARP subsidies (which are currently set to expire at the end of 2022), you'd only have to pay 3.6% of your income, or $1,080 for the year.

However, either way, the MLR rebate check you receive is still be based on the total premium, not the unsubsidized portion. The insurance carrier doesn't care one way or the other--they have to pay back that 1% excessive charge regardless.

That means that the $30K income subsidized enrollee should only really be receiving either 1/3 of that MLR refund ($24 instead of $72) or 15% of it ($11 instead of $72), depending on whether the ARP subsidies are in place or not. The other $48 or $61 should really be going to the U.S. treasury, since it's the one that paid for most of the premium in the first place.

Now, in this case, it's not that big of a deal...people getting $48 - $61 more than they "should" is pretty small potatoes and hardly worth making a fuss over. And up until 2017, this wasn't that big of a deal in most case.

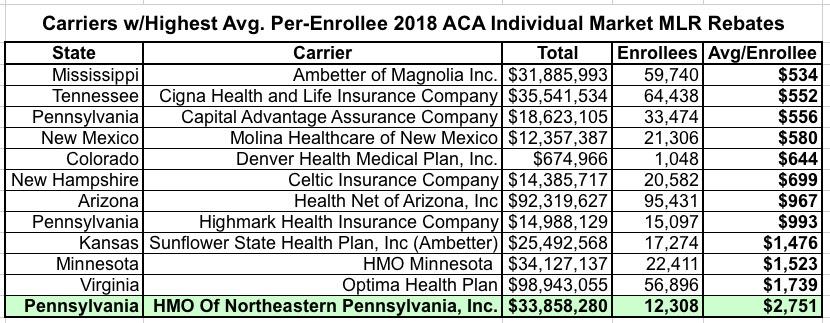

HOWEVER, things have changed dramatically starting with the 2018 rebates. Of the 67 carriers which owed Individual Market MLR rebates that year, over 25 of them owed an average rebate of at least $200 per enrollee. Twelve owed at least $500 per enrollee on average...and four of them owed over $1,000 to 109,000 enrollees apiece.

In fact, one carrier in particular, "HMO of Northeastern Pennsylvania, Inc." (operating as "First Priority Health HMO") had to pay an average of over $2,700 per enrollee to over 12,000 people:

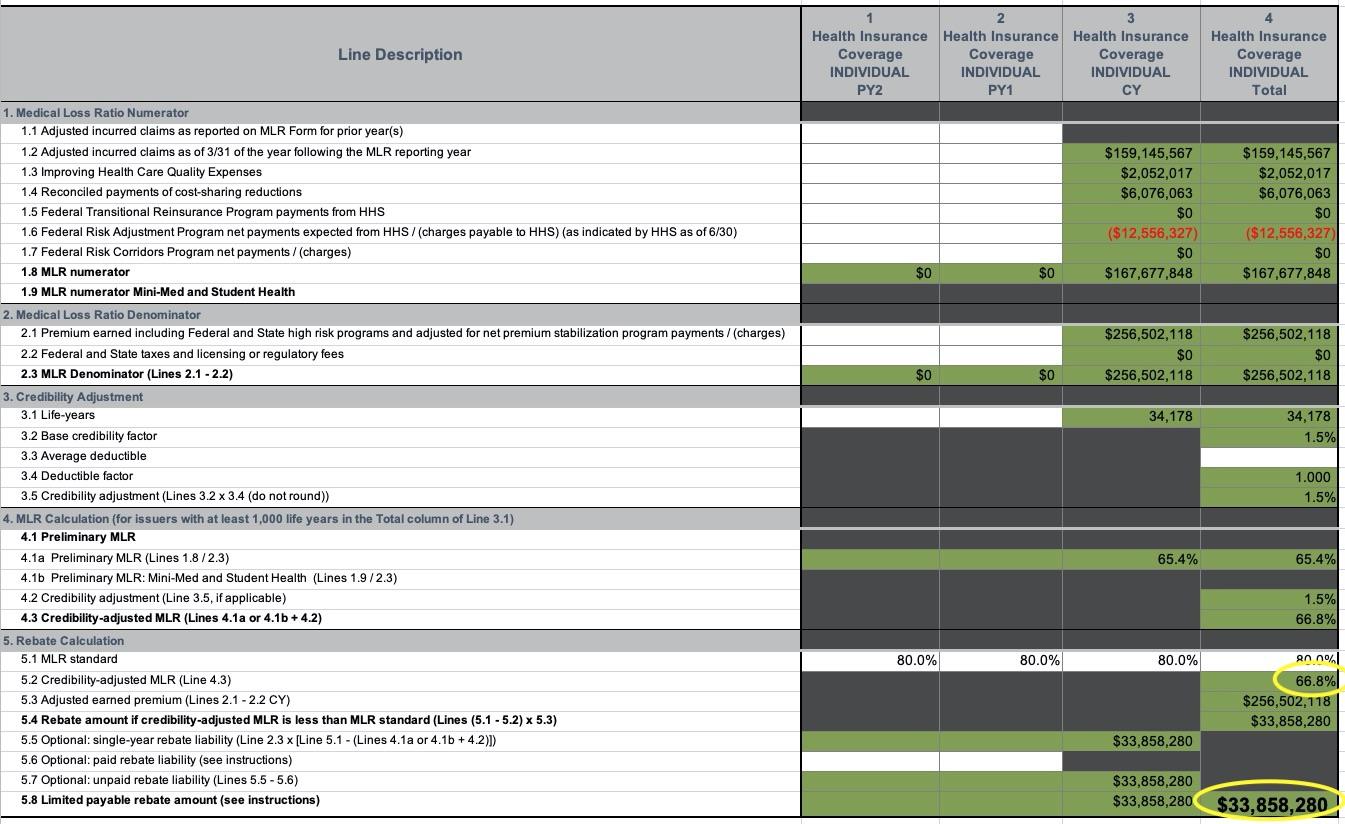

Remember, my example above assumes a measily 1% MLR rebate based on a 79% MLR...but there are some cases, especially in the past few years, where carriers have had to pay out far more. The Pennsylvania example shown above comes from the spreadsheet below--HMO of NE Pennsylvania had a 3-year average MLR of just 66.8% in 2018, which means they had to pay back a whopping 13.2% of their total premium revenue:

But wait, there's more! Remember, that $2,751 is just the average rebate amount. This means that some enrollees received far higher rebates...and in fact, that's exactly what started happening. Here's an actual email I received in 2019 (ID removed, of course):

I'm from Arizona. I just received an MLR rebate for $2,567 on a 2018 Ambetter subsidized plan for which I only paid $79/month in 2018. Am I really allowed to keep this money, or was there a mistake? Neither my accountant nor health insurance advisor knows the answer. The IRS website does not address who should be refunded when the plan is subsidized. It would be unbelievable stupidity if this law allows people to profit nearly 250% on a subsidized healthcare plan. I appreciate your help. Thanks!

Sure enough, this person paid just $948 in total premiums for their policy last year...but received a rebate check for $2,567. That's a net $1,619 profit.

Here's another forwarded by a broker friend of mine; the enrollee is also from Arizona (note: "Health Net of Arizona" is actually Ambetter):

I hope all is well with you and your family. This is nuts....I got a $1,648.60 check from Ambetter. Health Insurance Premium Rebate for Year 2018. Good Lord, I only paid maybe $75.00 in premiums for the whole year. I feel like I am participating in some forced scamming of the health care system. I think I asked you this last year, but is this for real? Will I be asked to repay this, somewhere down the line?

Again, that's a net $1,573 profit for this person.

Remember, these real world examples were from before the American Rescue Plan's enhanced subsidies, which brought net ACA premiums down to $0/month for all enrollees earning less than 150% of the Federal Poverty Level for 2021 & 2022, went into effect. Millions more are paying only nominal amounts after subsidies (CMS reported that 3.2 million HC.gov enrollees are paying $10/month or less this year).

This means that potentially a million or more ACA enrollees who paid nothing (or almost nothing) in premiums last year could end up receiving windfall checks of several thousand dollars apiece this August/September...because the federal government paid 100% of their premiums but 100% of the MLR rebate goes to the enrollees who hadn't paid a dime in premiums in the first place.

The solution to this is obvious, as Dave Anderson of Balloon-Juice noted at the time:

I think there is a good policy argument that the US Treasury should be at least a beneficiary of MLR rebates that are earned to individuals who receive APTC subsidies. The Treasury paid too much in APTC on the original round of insurance choice. Rejiggering the rebate formula so that MLR rebates are distributed in proportion to total paid premium by source could generate several hundred million dollars in pay-fors for the US Treasury.

In other words, if the APTC covers 90% of the premiums, 90% of the rebate check should be paid to the Treasury Dept. to reimburse them, with the other 10% going to the enrollees themselves. If APTC covers 30% of the enrollees premiums, 70% should go to the feds, and so on.

How much money are we talking about here?

Well, that's tough to say, as the total MLR rebate amount varies widely from year to year, as do the amount each carrier has to pay back. Some insurance carriers have probably never had to pay back MLR rebates, while others have had to make huge payouts for multiple years in a row. The whole point is to prevent them from price gouging and to try and do a more accurate projection of their actual overhead and claims for the coming year.

Having said that, if you assume an average total individual market MLR rebates of $500 million/year, and if you further assume that, say, 50% of that on average is being overpaid to subsidized enrollees, that means upwards of $250 million per year, or perhaps $2.5 billion over the next ten years.

Again, this may sound like small potatoes (the CBO projected that permanently extending the ARP subsidies themselves would cost around $220 billion over the next decade), but it's not chump change either. And it's exactly the type of rare cost-saving measure which is both good policy and good politics...especially if you're trying to get someone like Sen. Joe Manchin on board with making the ARP subsidies permanent.

How to support my healthcare wonkery:

1. Donate via ActBlue or PayPal

2. Subscribe via Substack.

3. Subscribe via Patreon.