There's a reason insurance carriers can't charge the unvaccinated higher premiums. It's called the ACA, and it's a good thing.

Over the past few weeks, as the Delta COVID-19 variant has surged across the country and COVID vaccination rates have plummeted, there's been a growing cry from many vaccinated Americans. Here's just a few examples:

Step up private sector. Mandate vaccinations for employees and consumers. Looking at you health insurance companies. Add insane premiums for those eligible yet refuse to be vaccinated. Deny hospital coverage for chosen unvaccinated hospital care.

— Ethan Embry (@EmbryEthan) August 3, 2021

It’s clear that new messaging—along with the obvious employer mandate—is having an impact.

Now’s a good time to require vaccines to fly.

Insurance companies should also raise premiums for the unvaccinated. Smokers pay more. Covid is more deadly than smoking—and it’s contagious. https://t.co/ob9d9ofoIn

— Angry Staffer (@Angry_Staffer) August 1, 2021

Wilfully unvaccinated need to pay the higher insurance premiums.

— I am a Kat! (@Katj512) August 3, 2021

...and so forth.

I originally planned on addressing this issue nearly two weeks ago, but got swamped with other matters and didn't get around to it until today.

Let's review.

Prior to the Affordable Care Act, private insurance carriers offering non-group or individual market healthcare plans to people who didn't have healthcare coverage through their employer and weren't eligible for Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP or other public healthcare programs had very little regulation in most states when it came to who they had to sell insurance to and how much they could charge them.

The way it generally worked was as follows:

- You'd have to fill out a mountain of paperwork detailing and documenting pretty much your entire medical history, including every doctor's visit, diagnosis, prescription drug, medical procedure and so forth, sometimes dating back decades, no matter how obscure or minor it was.

- You'd also have to fill out questionnaires regarding what you did for a living, your hobbies and personal habits such as smoking, alcohol use and so on.

- You'd have to provide the documentation for all of the above, including x-rays and the like, on your own time and out of your own pocket in many cases.

- You'd submit all of the above, and the insurance carrier would make you wait until they could review everything. This is a process known as "Medical Underwriting."

- If the insurance carrier decided that you were too "high risk" (that is, that you were likely to cost them a ton in medical claims), they would do one of the following:

- They might offer you an insurance policy, but at a significantly higher pemium rate than they charged customers they deemed to be "low risk".

- They might offer you an insurance policy at the same premium as they did for "low risk" people, but with an exception for certain types of coverage (that is, the policy might not cover a particular type of treatment or medication which it would for "low risk" enrollees)

- They might tell you to hit the road and refuse to offer you a policy at all.

- Even if they did offer you a policy and you were able to afford it, you might find yourself utterly screwed over a few years later if you submitted a pricey coverage claim for something which was included in the policy. This is due to a nasty practice called recission, in which an insurer would go over all your paperwork with a fine-toothed comb again, and if they found even the slightest error or omission (forgetting to mention that you had acne a decade ago, for instance), they would not only deny the claim, they would also retroactively cancel your entire policy. This often meant that you'd be denied insurance coverage at the exact moment that you needed it the most.

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT MADE ALL OF THE ABOVE ILLEGAL, including recission (except in cases of fraud or intentional misrepresentation).

Under the ACA, health insurance carriers are required to offer health insurance policies to anyone who wants to enroll in them; they aren't allowed to deny coverage to someone based on their medical condition, history, gender or so forth.

This is a policy known as "Guaranteed Issue".

Also, in order to be ACA-compliant, insurers must include a set of 10 core healthcare services with every policy they sell, and they have to be offered to every enrollee in that plan.

These are known as Essential Health Benefits.

Finally, under the ACA, health insurance carrers aren't allowed to charge some enrollees more than others based on their gender, medical history, medical condition, career, hobbies and so forth.

This is known as Community Rating.

In fact, under the ACA, health insurance premiums can only vary based on three criteria:

- Age (within a 3:1 range...a 64-yr old can only be charged up to 3x as much as a 21-yr old)

- Location (every state has one or more geographic "Rating Areas" where premiums may be higher or lower than other parts of the state)

- And finally...tobacco use. Insurance carriers can add up to a 50% surcharge for enrollees who smoke.

Even then, there are some states which are even stricter about these. For instance, in New York and Vermont, there is no age band at all: A 64-yr old is charged exactly the same as a 21-yr old (this is known as "pure" Community Rating), while in Massachusetts it's limited to a 2:1 ratio. There are 10 states where the smoking surcharge is limited to less than 50%, and in 7 of them it isn't allowed at all. Finally, some states have such a low population (or are so small geographically) that they have only a single Rating Area (Delaware, DC, Hawaii, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island & Vermont).

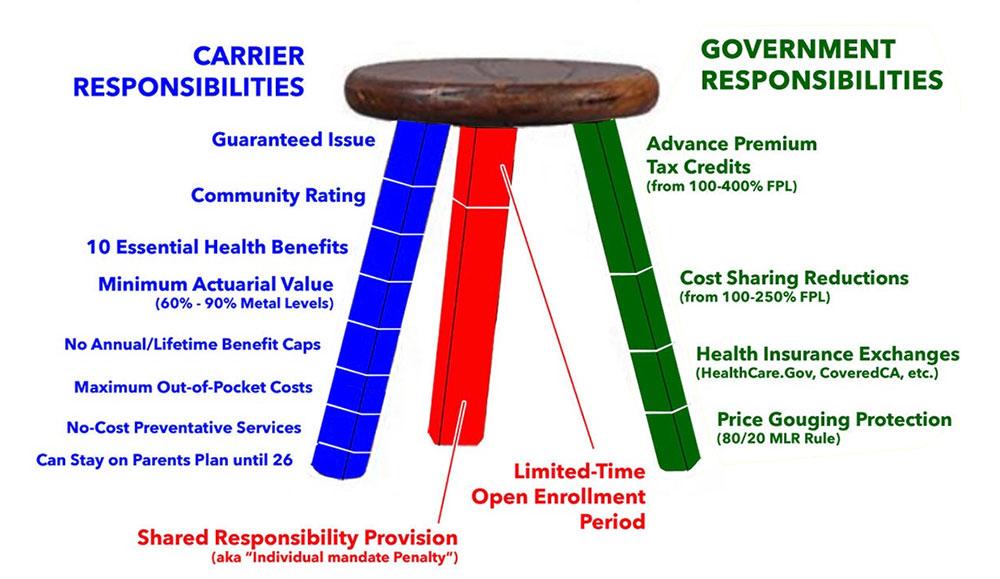

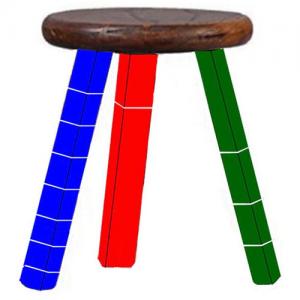

In any event, Guaranteed Issue, Community Rating and Essential Health Benefits comprise some of the most fundamental parts of the ACA's so-called "Three-Legged Stool." The version shown below is how it originally looked back in 2010:

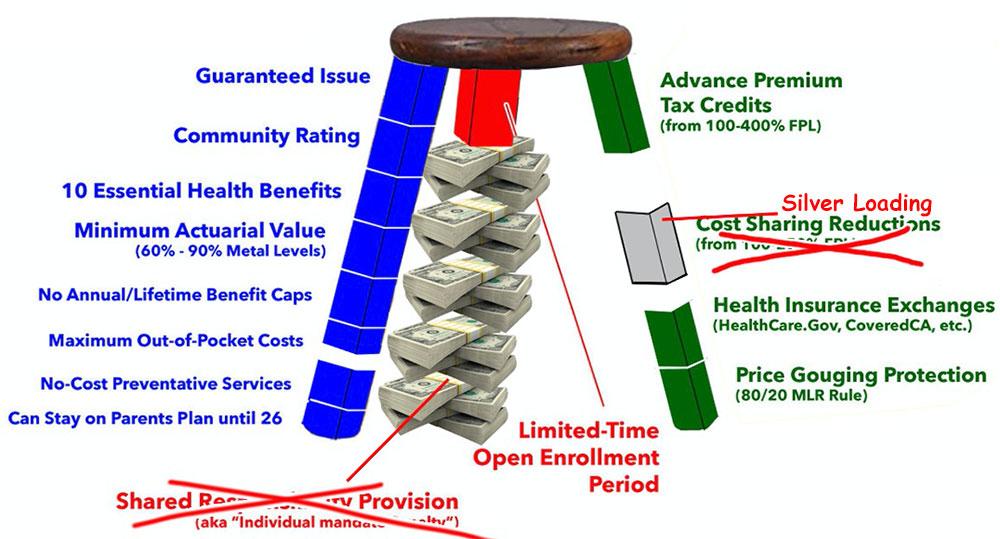

Now, there have certainly been some major changes to what the Stool looks like over the years. The Trump Administration attempted to kill off Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies, but that mostly backfired on him via a pricing strategy called "Silver Loading." Congressional Republicans eliminated the federal Individual Mandate Penalty, but this mostly just resulted in the federal government having to pony up billions of dollars more in financial subsidies to cover the increased costs.

These types of sabotage attempts, along with other shortcomings and weak points in the ACA structure itself, made the Stool look like more like this:

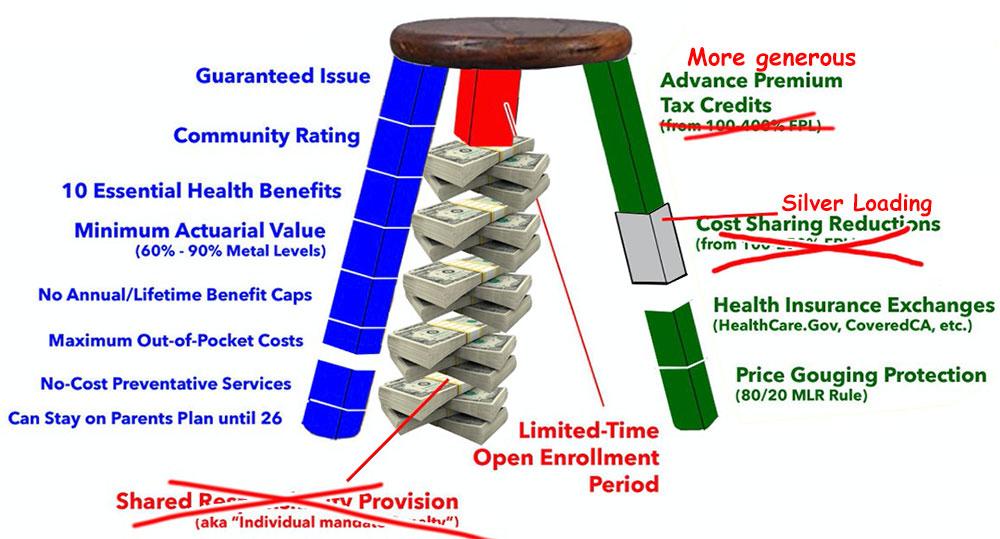

More recently, thanks to the American Resuce Plan passed by the Democratic Congress along with President Biden, one of the major holes in the 3-Legged Stool has been eliminated at least temporarily, meaning it looks like the following through at least the end of 2022:

Notice, however, that while there have been a lot of changes to the Green and Red legs of the ACA, the Blue Leg has remained mostly intact. There was a major threat to this by the Trump Administration via Seema Verma's "interpretation" of Section 1332 of the ACA, but that has fortunately been nipped in the bud by the Biden Administration.

In other words, the Blue Leg remains pretty much as it was intended. It comprises the bulk of the "Patient Protections" portion of the Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act.

The question today is whether or not the "Community Rating" section of the Blue Leg should be modified to add one more variable which insurance carriers are allowed to vary premiums on: Vaccination status.

Of the three currently allowed (age, rating area and tobacco use), the last one is the most relevant one to mention when it comes to the question of charging higher premiums for people who choose not to get vaccinated...because this is a behavorial choice as opposed to your age (something you have no control over) or where you live (ok, technically this is a choice, but it'd be a bit unreasonable to ask everyone living in Wyoming (home of the highest premiums in the country) to pack up and move to another state.

This morning, the New York Times laid out the case:

But insurers could try to do more, like penalizing the unvaccinated. And there is precedent. Already, some policies won’t cover treatment that results from what insurance companies deem risky behavior, such as scuba diving and rock climbing.

The Affordable Care Act allows insurers to charge smokers up to 50 percent more than what nonsmokers pay for some types of health plans. Four-fifths of states in the U.S. follow that protocol, though most employer-based plans do not do so. In 49 states, people who are caught driving without auto insurance face fines, confiscation of their car, loss of their license and even jail. And reckless drivers pay more for insurance.

The logic behind the policies is that the offenders’ behavior can hurt others and costs society a lot of money. If a person decides not to get vaccinated and contracts a bad case of Covid, they are not only exposing others in their workplace or neighborhoods; the tens or hundreds of thousands spent on their care could mean higher premiums for others as well in their insurance plans next year. What’s more, outbreaks in low-vaccination regions could help breed more vaccine-resistant variants that affect everyone.

On paper, this seems reasonable. However, this also starts to enter the "Slippery Slope" path. There are plenty of other personal choices people make which impact overall healthcare costs--eating fatty foods, having sex without a condom, etc.

Once you crack the door open to charge unvaccinated folks more, there will inevitably be a call for other behavorial decisions to be charged more as well...and if you think this might not impact you because you're a vaccinated vegan who always uses protection, keep in mind that in our modern, everything-online, everything-connected social media world, insurance carriers now have access to pretty much EVERYTHING about you. Why do you think CVS bought Aetna in the first place?

Prior to the proposed merger, Aetna was notable among leading insurers for not selling anonymized patient data. By contrast, CVS, like many pharmacy chains, has long sold and traded prescription records without patient names to medical data mining companies such as IMS Health, which in November renamed itself IQVIA.

...Privacy experts say that the more anonymized information one gathers from multiple sources, the easier it becomes to re-identify a person. For example, an outsider might be able to puzzle out which dossier belongs to an anonymous patient just by knowing where they have lived over time. It’s entirely possible that the last three cities where I have lived—Fairbanks, Alaska, the Boston area, and Belgrade, Serbia—uniquely identify me.

Setting that aside, there are other reasons to think twice before cracking open the Community Rating gate, laid out by Dania Palanker of the Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms:

I am really confused by the policy suggestion to increase insurance premiums on the unvaccinated. Vaccination rate is about 15% lower for Black people than for white people. People with lower incomes are more likely to be unvaccinated.

And seriously citing to short-term health plans excluding coverage based on risky behavior as an example? Really? Are we going to suggest the marketplaces exclude coverage to unvaccinated who have had COVID because short-term health plans do?

We just made health care more affordable for millions of people - to increase access to health care but also to help people financially. So we raise health costs now, as we are still struggling to recover?

What about the worker who can't figure out how to get to a vaccination site between her shifts and childcare? The person who has lived a life of discrimination from the health care system? The disabled senior who has yet to get transportation to a vaccination site?

This is a contentious issue, and I fully understand the desire to punish those who voluntarily choose not to get vaccinated...but as Palanker notes, there's a big difference between someone who could easily do so but chooses not to and someone who wants to but has legitimate barriers preventing them from it. There are far fewer barriers than there once were, but even so, how is an insurance carrier to tell the difference?

For that matter, I don't know that it would make much difference in behavior regardless. There hasn't been much written about how successful the ACA's smoker surcharge is, but according to one study from 2016, the answer is "not very":

To account for tobacco users' excess health care costs and encourage cessation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allowed marketplace plans to impose a surcharge on tobacco users' premiums. Because tax credits were calculated from premiums for non-tobacco-users, this policy greatly increased many smokers' out-of-pocket costs. Using data from the 2011-2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, we examined the effect of tobacco surcharges on insurance coverage and smoking cessation in the first year of marketplace implementation, among adults most likely to purchase insurance from state marketplaces. Relative to those facing no surcharges, smokers facing medium or high surcharges had significantly reduced insurance coverage (-4.3 to -11.6 percentage points), but no significant differences in smoking cessation.

In contrast, those facing low surcharges showed significantly reduced smoking cessation. Taken together, these findings suggest that tobacco surcharges conflicted with a major goal of the ACA – increased financial protection – without increasing smoking cessation. States should consider these potential effects when deciding whether to constrain the surcharge below the federal limit in the future.

In other words, if the goal of jacking up insurance rates for the unvaccinated is to get them to get vaccinated, it's not likely to do much good.

This makes sense if you think about it: A bunch of states have been literally giving away millions of dollars in vaccination sweepstakes without it seeming to have much impact. If financial gain won't get someone to get the jab, I don't know that the threat of financial loss will do much either.

Having said that, those who don't get vaccinated will start facing more financial penalties soon anyway...a point which is included in the NY Times article above itself:

In 2020, before there were Covid-19 vaccines, most major private insurers waived patient payments — from coinsurance to deductibles — for Covid treatment. But many if not most have allowed that policy to lapse. Aetna, for example, ended that policy on Feb. 28; UnitedHealthcare began rolling back its waivers late last year and discontinued them by the end of March.

UPDATE: I should note that regardless of the "big picture" question of whether to allow a "not-vaxxed exception" in general, there's also a far more practical reason why it would be rather pointless at the moment: Any such change wouldn't have any impact on insurance premiums until January 2023 at the earliest anyway...and if we haven't reached herd immunity by then, we're pretty much screwed, and charging a few thousand bucks extra to those remaining unvaccinated won't do anything to stop that.

As an aside, while it's reasonable to discuss whether the ACA should be altered to allow higher premiums for the unvaccinated, I'm deeply dismayed that so many people seemed to think that this was already allowed. Pretty much the entire 2017 "Repeal/Replace Obamacare!" debacle was specifically focused on protecting the three Blue Leg Tenets above: Guaranteed Issue, Community Rating and Essential Health Benefits. I know it's been a few years but are people's memories really that short?

UPDATE x2: Within an hour of my posting this piece, someone on Twitter made my exact point for me:

Need to charge more for overweight first…

— Chad Williams (@thechadwilliams) August 3, 2021