UPDATE: If you thought the ACA's MLR rebates were huge last summer, you may not have seen anything yet...

Back in December, Congress passed, and Donald Trump signed, a $1.4 Trillion federal spending package which included, among other things, the permanent elimination of several taxes which had been established to help fund the Affordable Care Act:

The Cadillac Tax: As Newsweek reported in 2017, the so-called "Cadillac tax" would have capped the tax deductions individuals could claim based on their health insurance benefits. It would have imposed a 40 percent excise tax on employer-sponsored plans that exceeded $10,000 in premiums per year for a single person or $27,500 for a family. The Cadillac tax was set to take effect in 2022.

The elimination of the Cadillac Tax is hardly surprising; it's faced wide bipartisan opposition since the moment it was added to the ACA. Republicans opposed it because they hate taxes, of course, while many unions opposed it for a similar reason to their opposition of Medicare for All: They've given up a lot of other concessions over the years in return for high-end healthcare coverage, and had no intention of seeing those platinum policies taxed (and certainly not at a 40% rate).

As a result, the Cadillac tax has never actually been enforced anyway. Every year or two Congress would pass a bill pushing the implementation date down the road, to the point that it became a running joke. All the December bill does is acknowledge what everyone knew already: It was doomed from the start.

Personally, I think the employer-based insurance tax exemption should be eliminated altogether--it's the main reason why the U.S. has been locked into the current fractured healthcare coverage system in the first place--but if they're gonna do it, it shouldn't be limited to high-end policies alone.

I've flipped the 2nd and 3rd items in the article around deliberately:

The Medical Device Tax: ...the medical device tax was a 2.3 percent excise tax on gross sales of medical devices used by humans (not animals) such as x-ray machines and hospital beds. It was implemented in 2013 but had been suspended since 2015, according to the Tax Foundation.

Similar to the Cadillac tax (which has never been enforced), the Medical Device Tax hasn't been enforced for the past four years anyway. The elimination of it in the spending bill actually surprised me, however...but only because I thought it had already been permanently repealed. Apparently I was wrong...until now.

And finally, we come to the point of this blog entry:

The Health Insurance Tax: Suspended in 2019, the health insurance tax will reappear in 2020 before disappearing for good in 2021. The tax has imposed a yearly fee on insurance companies that provide health policies, including "individual policies, small groups, non self-insured employers, Medicaid managed care, Medicare Part D, and Medicare Advantage," according to Center Forward, a political action committee.

Unlike the first two taxes above, the Health Insurance Tax (HIT) has been alternately enforced, then not enforced, then enforced again...it's basically been doing the Hokey Pokey for years now, to the point that I can no longer remember which years it was charged and which years it was suspended. While increasing the federal deficit even more isn't a good thing, I'm at least relieved that Congress finally decided definitively one way or the other; it was getting confusing trying to keep track.

HERE'S THE MULTI-BILLION DOLLAR QUESTION, and the whole point of this article: Is the HIT being collected by the IRS for 2020 premiums or not?

I've been engaged in a raging wonk fest discussion about this all morning with my colleagues Dave Anderson, Louise Norris and Colin Baillio, and for the life of me I can't figure it out.

Here's the relevant portion of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2020" (aka the federal spending bill from last December):

SEC. 502. REPEAL OF ANNUAL FEE ON HEALTH INSURANCE PROVIDERS.

(a) IN GENERAL.—Subtitle A of title IX of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is amended by striking section 9010.

(b) EFFECTIVE DATE.—The amendment made by this section shall apply to calendar years beginning after December 31, 2020.

OK, but does that mean the tax won't be collected after 2020 or that it won't be charged for 2020?

Louise Norris pointed me towards this FAQ on the IRS's website:

Section 9010 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) imposes a fee on each covered entity engaged in the business of providing health insurance for United States health risks. The first filings were due from covered entities by April 15, 2014 and the first fees were due September 30, 2014. There was a moratorium on the fee for 2017 and there was a suspension on the fee for 2019. The fee was repealed for calendar years beginning after December 31, 2020.

The repeal of the Health Insurance Providers Fee is for fee years AFTER 2020 NOT for fee year 2020

The due date for Form 8963, Report of Health Insurance Provider Information, for Fee Year 2020 is April 15, 2020.

Q1: Does repeal of the fee for calendar years beginning after December 31, 2020 (the “Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, Division N, Subtitle E § 502”), affect the 2020 fee year?

A1: No. Form 8963 for the 2020 fee year is due by April 15, 2020. The applicable amount for fee year 2020 is $15, 522,820,037

Q2: Under the 2019 suspension, was there a health insurance provider fee in 2019?

A2: No. There was no fee in 2019. There is a fee in 2020. There is no fee after the 2020 fee year (2021 calendar year).

Q3: Did the 2017 moratorium or 2019 suspension affect the 2018 or 2020 fee years? Does the repeal after the 2020 fee year affect the 2020 fee year?

A3: No. Form 8963 for the 2018 fee year was due by April 17, 2018. The 2018 applicable amount was $14.3 billion, and any required payment was due on September 30, 2018. Form 8963 for the 2020 fee year is due by April 15, 2020. The applicable amount for fee year 2020 is $15,522,820,037, and any required payment is due on September 30, 2020.

All of this makes it sound, at first read, as if yes, the IRS will be collecting the tax for 2020, but that raises the question of how they can know the amount if they're filling out the form for it and paying it in the same calendar year that it's being charged for?

Louise gives this explanation:

They figure out the amount in advance, and then divide it up across the insurers. That's why it's not a set percentage from one year to the next.

That IRS FAQ page says the payment for fee year 2020 is due September 30, 2020. According to Section 9010, it seems like the fee year is the current year, and the fee amount is based on premiums from the prior year.

HOWEVER, Colin explains it this way:

So keep in mind, when you see FEE YEAR it means the fees collected for the prior year

...Fee year 2020 gets paid in Sept 2020 on 2019 premiums

...which led Louise to re-think her view:

So now I've gotten myself all confused again... is the payment that's due in September 2020 the last one they'll have to pay? If so, then it seems like Colin is right, since the amount they're paying this coming fall will be based on premiums from last year. And there's no more "fee years" after this year.

...OK, that makes sense. And now all of the various documents — the repeal bill, Section 9010, and the IRS page and FAQs — seem to point to the same thing... that the fee being collected this coming fall will be the last one. And from the wording of that CT bulletin, it sounds like insurers do bake the cost into their current year premiums to cover the fee for the coming year (which makes sense, since those are the applicable premiums). So we can assume that insurers all across the country incorporated the fee they expected to pay in September 2021 into the premiums they're charging in 2020?

..."Fee year" is clarified here too...Definitely the year in which the fee is paid, and based on premiums from the prior year.

Yeesh. The answer to this question is really important for several reasons. I'm focusing on the first of these reasons in this post.

The spending bill wasn't passed until December, while insurance carriers nationally assumed that the HIT would be charged when they set their 2020 premium rates last summer. IF it's correct that the HIT fees will not be collected by the IRS for calendar year 2020 premiums, that means that the carriers set their premiums around 2.2% higher for 2020 than it turned out that they needed to.

Normally this might cause the average consumer to be outraged...except that thanks to the ACA's Medical Loss Ratio rule, a big chunk of that ~2.2% should end up being rebated back to the policyholders on a 3-year rotating average basis in 2021, 2022 & 2023.

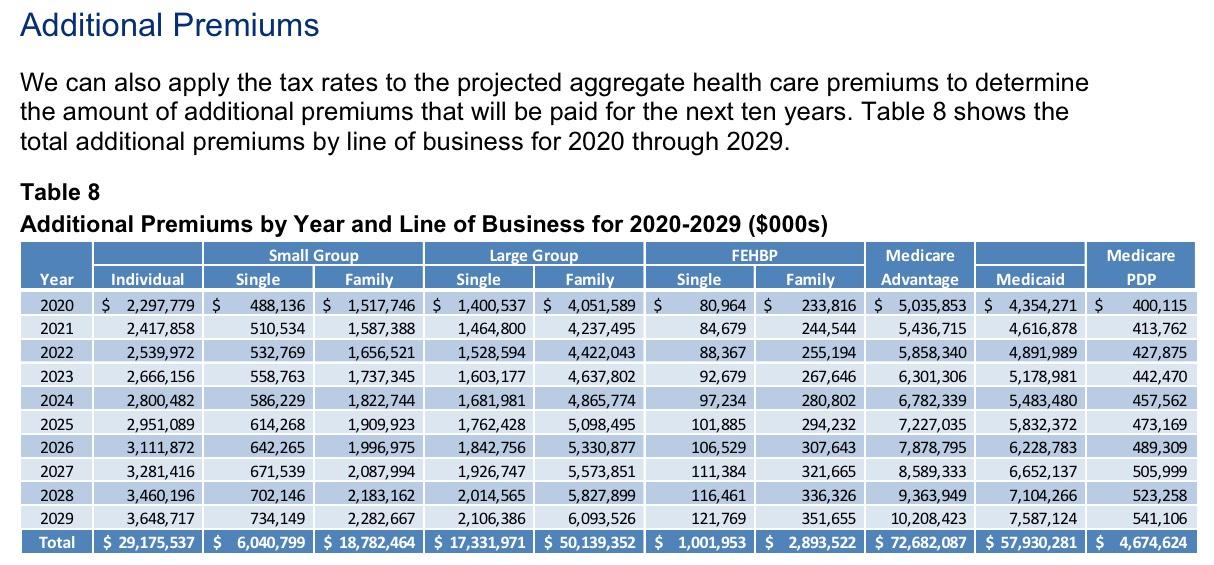

First of all, just how much money are we talking about here? Well, the formula gets a little wonky, but this analysis from Oliver Wyman projected the following (assuming the tax wasn't repealed and was actually collected each year going forward, of course):

These are the additional premiums added due to the tax. This is actually higher than the amount of the tax itself, because, as Oliver Wyman explains:

The taxes on health insurance are non-deductible for federal tax purposes for health insurers. Therefore, for each dollar assessed and paid in taxes, more than a dollar in additional premiums must be collected (e.g. $1.27 for every $1.00 in taxes, assuming a 21% federal corporate income tax rate) yielding a total premium impact in 2020 of as much as $20.3 billion. In total, the amount assessed and collected is projected to be over $260 billion over the ten-year period of 2020 to 2029.

For purposes of this blog entry, 2020 is the only year that's relevant anymore (other than the increase of $260 billion to the federal debt, which is utterly out of control at this point anyway). I'm not going to go into the other programs listed (FEHBP, Medicare and Medicaid) because those are handled completely differently by the MLR rule (I'm actually not sure about how FEHBP is handled, actually), but take a look at the Indy and Group markets:

- $2.3 billion on the Individual Market

- $2.0 billion on the Small Group Market

- $5.4 billion on the Large Group Market

- $9.7 billion total

Holy Crap. Does this mean that policyholders are going to see a $9.7 billion windfall in 2021? No, not quite. First of all, these are just projections from 2018 for calendar year 2020; the actual amounts could be higher or lower. Secondly, as I explain in my MLR tutorials, MLR rebates are calculated based on a formula involving a 3-year rotating average basis. This means that at most, up to ~$3.2 billion would be rebated in each year (2021, 2022, 2023) based on the HIT repeal.

Furthermore, not all of this "bonus" money would be subject to MLR rules anyway. There are exceptions and adjustments to the rule based on carrier size, average deductible of the policies offered and so forth. For instance, if a carrier has fewer than 1,000 people covered over the 3 year period (averaging fewer than 333/year), they're exempt from the MLR rule entirely; if they're larger than that but below 75,000 "life years" the formula is adjusted on a sliding scale, and so on.

Finally, remember that in order for a rebate to be required, the carrier's 3-year rotating average gross margin has to total more than 20% of their revenue for the individual and small group markets, or more than 15% for the large group market. Any carrier which ends up seeing their MLR hit or exceed 80% / 85% respectively after all the adjustments are made doesn't have to pay back anything...and even if they fall below that, they only have to rebate as much money as it takes to hit the 80/85% threshold.

HAVING SAID ALL THAT, it's still extremely likely that a big chunk of that $9.7 billion will end up being rebated to policyholders over a 3-year period.

But I'm not done yet.

In my MLR Rebate Project last summer, I (mostly) accurately calculated that around $770 million would be rebated to around 3.7 million Individual Market enrollees for 2018, averaging around $208 per enrollee. In addition, around $311 million was rebated to 3.0 million small group enrollees, and $290 million to 2.3 million large group enrollees, for a total of $1.37 billion being paid back to 8.6 million people, averaging $159 apiece.

I further projected that for the 2019 MLR rebates (to be paid out in August/September 2020), while there probably won't be much change in the small or large group markets, the individual market rebates could potentially be as much as double what they were last year--up to $1.7 billion on the indy market alone...and due to the 3-year rotating average, a lot of this excess would likely still carry over into 2021...and that's before the HIT repeal is taken into account.

BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE...MAYBE.

Remember, there's also two other major wildcards, both surrounding federal class action lawsuits being brought by various insurance carriers against the federal government. I'm not going to rehash either of these here since I already did in-depth analyses of both last year, but I strongly advise reading them both:

The bottom line is that if these lawsuits are ultimately successful (and so far they seem to be), and if the federal government is actually required to pay out the billions of dollars that they're legally and contractually required to dating as far back as 2015 (for Risk Corridor payments) or 2017 (for CSR payments), then there's a strong possibility that some carriers will end up having to pay back billions of dollars MORE in MLR rebates on top of everything else I just described.

The exact timing of all of this is uncertain, however, due not only to the 3-year rotating average and the unknown timing of the judicial proceedings, but also to not knowing how the carriers will have to enter the settlement revenue. If it's done on a "cash basis", then it'll be a one-time windfall counted as part of whatever year the payment is made. If it's not done that way, the carriers would have to back-date their 2017 and 2018 financial records, then figure out what portion of the additional funds has to be paid to each policyholder (not a fun task!) on top of whatever payments were already made in 2018, 2019 & 2020.

It could get very messy, but the bottom line is that a whole bunch of ACA sabotage efforts by the GOP may end up running headfirst into the ACA's MLR rebate rule, resulting in millions of policyholders potentially looking at some massive rebate checks over the next few years. In fact, some of them may end up actually profiting off of it all.

Stay tuned...

UPDATE: Read this explainer from my friend Wesley Sanders (who works for a Georgia-based insurance carrier) and tell me if it makes things more or less clear:

[HIT] will be collected for 2020 premiums and MLR for plan year 2020 will be impacted. It's based on 2019 premiums but for MLR and GAAP purposes it counts as a 2020 expense.

It's a super maddening method. the way it gets expensed is a violation of the matching principle of accounting in my opinion but FASB and the NAIC get to make that call, not me.

The rationale for why you would expense it the year after the premiums occur is that if you wrote premiums in 2019 but then ceased to exist in 2020, you would ultimately not owe the fee because you have to be still operating as an insurer in the fee year

So the tax, though calculated based on 2019 premiums, is actually incurred by your continuing to operate in 2020

CMS generally aligns with the NAIC statutory accounting principles where possible in the MLR filing, so the section 9010 fee will count against MLR in 2020. For 2019, no MLR impact will be recorded.

UPDATE: This from Jason Levitis of the Brookings Institute, who also led the implementation of the ACA at the U.S. Treasury Dept., seems to be a pretty damned definitiive answer:

The federal fee will be paid for the last time in Sept. 2020, and that payment will be based on 2019 premiums. State Health & Value Strategies has posted a resource on this for states considering a state fee to pick up the revenue. https://t.co/WY3GgeB3Fl @HeatherHHoward

— Jason A. Levitis (@jasonlevitis) February 19, 2020

So there you have it: Upwards of $9.7 billion will either end up being split between the insurance carriers and the policyholders or it will be repurposed into more equitable, more efficient form of healthcare cost savings by the states...if they act quickly. My next post will focus on this last possibility, which hopefully is about to become reality in New Mexico...