New VA/NM policies reignite burning questions re. the ACA & smoking

Way back in the Before Times® of 2015, fellow healthcare policy wonk Andrew Sprung (aka Xpostfactoid) posed an interesting question:

Do any ACA marketplace enrollees (or off-exchange enrollees for that matter) actually confess to being smokers? Why would you?

— xpostfactoid (@xpostfactoid1) November 13, 2015

Before the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies could use medical underwriting, along with the threat of rescission, to tell whether a new policy applicant was being truthful or not about their smoking status. Under the ACA, it's illegal for insurance companies to ask any questions about your health or medical history or pre-existing conditions which you might have...with a few exceptions, the main ones being a) whether anyone on the policy is pregnant and b) whether anyone on the policy is a smoker. (The question re. pregnancy can't be used to either deny coverage or charge more for it; I believe that's only included to determine whether the pregnant woman is eligible for Medicaid instead of subsidized ACA coverage).

Here's a summary of the smoking situation under the ACA:

Although insurers can’t charge more for health status, they can charge up to 50% more for smoking status. On the flip side of this ObamaCare includes smoking cessation therapy (including medication) as a free preventive service on all non-grandfathered plans sold since September 23, 2010.

ObamaCare makes it so you can’t be denied coverage for being a smoker now or in the past.

Small group plans offered by small employers must also cover smoking cessation. Typically Medicaid, Medicare, and large group plans also offer smoking cessation therapy.

Short term plans and other plans not considered major medical coverage don’t have to follow the same rules in regards to smoking. As such you can be denied short term coverage for being a smoker and don’t have to be given free cessation therapy.

Extra specialized cessation therapy is offered to pregnant women.

In general you count as a smoker if you use tobacco four or more days a week for the past 6 months. If you are quitting, or smoke once in a while, or use tobacco for ceremonies, you may not qualify as a smoker.

You must report whether or not you are a smoker. Giving the information is based on the honor system, however you can be denied coverage due to fraud or misrepresentation, so answer honestly.

ObamaCare says smokers can be charged up to 50% more for their premiums. This is due to a “tobacco surcharge”.

Those on employer health plans can avoid the surcharge by joining an employer based tobacco cessation program.

The tobacco premium surcharge is calculated after cost assistance, not before.

Statistically, lower-income Americans are the most likely group to smoke.

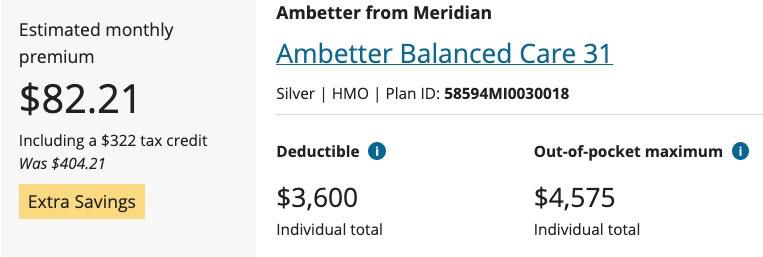

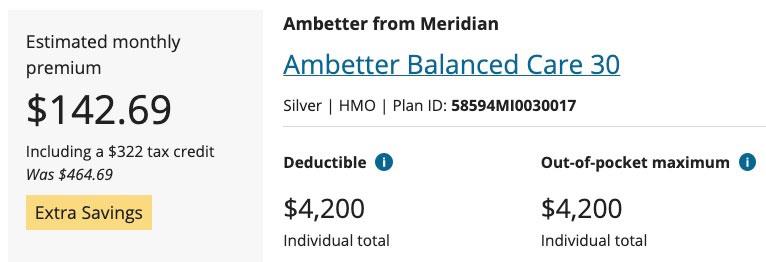

The 2nd-to-last bullet above is the real killer (no pun intended): The smoker surcharge is not included when your tax credits are calculated. Here's an example of how big a difference this can make: A 50-year old single adult earning $30,000/year in Oakland County, Michigan. It's important to note that Ambetter appears to only charge a 15% smoker surcharge, far less than the 50% that they're allowed to under the Affordable Care Act:

At full price, the premium would be $465/month for a smoker, 15% higher than the $404/month the same enrollee has to pay if they don't smoke.

At $30K/year, however, this enrollee would receive the same $322/month tax credit either way. While this drops the net premium dramatically in both scenarios, it would now cost them 74% more if they check off the "smoker" box than if they don't, because that extra $61/month is applied no matter what their income is.

And again, this is with just a 15% surcharge; if Ambetter was charging the full 50%, the smoker would have to pay a whopping $202/month more than the nonsmoker...or nearly 3.5x as much after subsidies if they earn $30K/year ($284/mo vs. $82/mo).

As Sprung asked nearly seven years ago: How many smokers signing up for individual coverage--whether on or off the ACA exchanges--are actually being honest about their response? I don't recall seeing any information about this in any of the official HHS Dept. ASPE reports, and even at the state exchange level, I don't think the percentage/number of smokers has been included even in highly detailed enrollment reports.

The discussion in response to his question at the time ranged from "I dunno" to "I think you just have to pay the back tobacco surcharge if they find out". It'd be interesting to learn the answer.

According to the Centers for Disease Control:

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States, accounting for more than 480,000 deaths every year, or about 1 in 5 deaths.

For what it's worth, there were around 361,000 U.S. deaths in 2020, and around 494,000 in 2021, also according to the CDC.

In 2020, nearly 13 of every 100 U.S. adults aged 18 years or older (12.5%) currently* smoked cigarettes. This means an estimated 30.8 million adults in the United States currently smoke cigarettes. More than 16 million Americans live with a smoking-related disease.

The good news is that...

Current smoking has declined from 20.9% (nearly 21 of every 100 adults) in 2005 to 12.5% (nearly 13 of every 100 adults) in 2020.

*Current smokers are defined as people who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and who, at the time they participated in a survey about this topic, reported smoking every day or some days.

The bad news is that...

Current cigarette smoking was highest in uninsured adults and adults insured by Medicaid and lowest in adults with private insurance.

- Nearly 23 of every 100 adults insured by Medicaid (22.7%)

- About 21 of every 100 adults who were uninsured (21.2%)

- Nearly 15 of every 100 adults who had other public insurance (14.8%)

- About 10 of every 100 adults insured by Medicare only (10.2%)

- About 9 of every 100 adults with private insurance (9.2%)

I'm not going to delve into the dynamics of higher smoking rates among the uninsured and Medicaid populations in this piece. I'm focusing purely on thr 9.2% of private insurance enrollees who smoke.

Unfortunately, this study doesn't distinguish between those with private employer-based health insurance (which is something like 45% of the total U.S. population) and those with individual market health insurance (which is less than 5% of the U.S. population), but assuming the ratio is similar, that means something like 1.3 million ACA exchange enrollees (out of the ~14 million total effectuated) are smokers, give or take.

OK, so setting aside the "just lie about it" factor, what's the actual impact of the ACA's tobacco surcharge in practice?

Well, back in 2016 there was a big study published at Health Affairs on this very issue which concluded:

As expected, nonsmokers exhibited an increase in their likelihood of having insurance after Marketplace implementation that did not differ by the size of the tobacco surcharge...For smokers, however, larger tobacco surcharges dampened the increase in insurance coverage associated with the exchanges’ implementation. Indeed, Exhibit 2 shows no increase in coverage for a representative smoker at the “high” surcharge level.

The results in Exhibit 3 under model 1 are from the regressions used to generate Exhibit 2 . These results represent the differential impact of surcharge size on smokers’ 2014 insurance coverage, relative to the effect on smokers in the zero-surcharge group. Regardless of age group, low surcharges yielded a statistically insignificant drop in smokers’ health insurance take-up in 2014, relative to the zero-surcharge group. These effects grew and became statistically significant as surcharge levels rose, reaching −11.6 percentage points in the group with a high surcharge. At every surcharge level, effects were even larger in the subsample younger than age forty.

OK, so as you might expect, a draconian surcharge strongly discouraged potential enrollees from signing up for health insurance coverage. If your primary goal is to get as many people healthcare coverage as possible, that's bad. If your primary goal is to keep the risk pool healthier by weeding out more at-risk enrollees...well, mission accomplished, I guess. The problem is that this runs completely contrary to one of the major points of the ACA.

In addition, ironically, the higher tobacco surcharges may actually backfire even on the risk pool level:

...While reduced insurance take-up is not a surprising response to higher surcharges, it is concerning. Smokers were 7.3 percentage points less likely than nonsmokers to have coverage...so smokers’ enrollment is critical to achieving universal coverage. Moreover, as younger adults’ enrollment in exchange plans is important for risk pooling, the large effects found among smokers younger than age forty may have broad implications for the long-term stability of Marketplaces in states with high surcharge levels.

As for the other reason given for including a tobacco surchage--helping goad people into quitting smoking:

...Among the groups with zero, medium, or high surcharges, the exchange implementation’s effects on smoking cessation were neither substantive nor statistically different from each other. However, relative to members of every other surcharge group, those facing low (but nonzero) surcharges were significantly less likely to quit smoking. Among the nonzero-surcharge groups, the fact that those with higher surcharges showed a greater likelihood of quitting than the those in the group with low surcharges, despite having no gains in coverage, suggests a direct response to surcharge size (that is, a tendency to respond to a high smoking penalty by quitting, conditional on the imposition of a nonzero penalty).

...However, neither of these competing mechanisms explains why people with low surcharges exhibited a decline in smoking cessation relative to those with no surcharge, when both groups showed similar increases in insurance coverage ( Exhibit 3 ). One possible explanation is that putting a price on bad behaviors can alleviate the guilt of engaging in them, which has an unexpected effect: The behaviors increase. In one famous illustration, instituting a fee for late pick-up at an Israeli day care center resulted in more, not fewer, tardy caregivers.

The study also addressed the "improve the risk pool" factor and finds an ugly "bonus" under the surface for carriers:

...One purpose of the surcharges is to have tobacco users pay for the excess health costs associated with their smoking. Yet Kaplan and coauthors found that surcharges were often significantly greater than smoking’s added health care costs. As people with psychological distress or depression have much higher smoking rates than those without mental health conditions (34 percent versus 17 percent), some insurers could be using the tobacco surcharges to discourage enrollment by patients with high-cost conditions. If the risk-adjustment mechanism in a state’s exchange does not adequately compensate plans for these disease states, insurers may profit by encouraging such adverse selection.

Thus, an unintended consequence of tobacco surcharges may be reduced coverage (or unfairly high premiums) for some individuals with persistently high health care costs unrelated to their tobacco use. Such individuals might have benefited greatly from gaining coverage. When considering the effects of tobacco surcharges, policy makers should account for such costs.

Of course that was in 2016, some six years ago. What about today? Well, a similar, updated study was published at Health Affairs just last month, and while it's not publicly available, the conclusion seems to be pretty much the same:

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows insurers to charge tobacco users who have nongroup coverage up to 50 percent more than nonusers of tobacco. In this study we used 2014–19 administrative data on enrollees in the federally facilitated ACA Marketplace, HealthCare.gov, to examine the relationships among surcharge rates, total Marketplace enrollment, and enrollment by tobacco users. We found that the tobacco surcharge rate averaged approximately 14 percent and that it was associated with lower total enrollment as well as a reduced share of total enrollees who reported any tobacco use. Our analysis also found that tobacco surcharges have a significantly larger effect on tobacco users’ share of enrollment in rural areas than in urban areas, which may in turn contribute to urban-rural health disparities. Given that tobacco surcharges may decrease Marketplace enrollment overall and shift the composition of enrollment away from tobacco users, our findings suggest that reducing tobacco surcharges may increase total Marketplace enrollment.

As it happens, while the ACA itself currently allows up to a 50% smoking surcharge, there's nine states + DC which either restrict it to less than 50% or which don't allow any tobacco surcharge at all...some of which may be surprising:

- Arkansas: 20% surcharge allowed

- California: no surcharge allowed

- Colorado: 15% surchare allowed

- District of Columbia: no surcharge allowed

- Kentucky: 40% surcharge allowed

- Massachusetts: no surcharge allowed

- New Jersey: no surcharge allowed

- New York: no surcharge allowed

- Rhode Island: no surcharge allowed

- Vermont: 1% surcharge allowed

(Connecticut has a 50% tobacco surcharge cap but that's the same as the ACA's so it's not terribly relevant here).

Well, in light of the two studies I highlighted above, it looks like at least two more states have been paying attention as well.

In VIRGINIA, as reported by Louise Norris over at healthinsurance.org:

Insurers will not be allowed to impose a tobacco surcharge as of 2023. This is due to legislation (HB675/SB422) that passed both chambers of the state legislature in early 2022. The governor had not signed the bills as of late March, but the SCC/BOI informed insurers that tobacco surcharges will not be allowed. The ACA allows health insurance companies to charge tobacco users up to 50% more in premiums, but Virginia is joining several other states that prohibit or limit tobacco surcharges.

Meanwhile, in NEW MEXICO, Colin Baillio, project director of the New Mexico Insurance Dept, chimed in as well:

Due to mounting evidence that tobacco rating in the individual market suppresses enrollment, undermines financial protection afforded by coverage, and has disproportionate negative impacts rural communities, OSI is requiring issuers to set the tobacco rating multiplier at 1.0 for all individual on-and-off-exchange plans that will be offered during the 2023 plan year. This applies only to the individual market.

Confirm the tobacco factors are within the required 1.5:1 range for small group offerings. Explain differences in the tobacco use factors from the prior approved filing. Provide support for the tobacco use calibration.

In other words, the 50% surcharge is staying in place for New Mexico's small group market (for now), but it's being eliminated for the individual (ACA exchange) market starting next year.

Hopefully more states will follow, and it'd be helpful if the ACA itself was revised to eliminate the tobacco surcharge across every state. Not vital, but helpful.

How to support my healthcare wonkery:

1. Donate via ActBlue or PayPal

2. Subscribe via Substack.

3. Subscribe via Patreon.