UPDATED: How much can risk pools vary? Here's a stunning real-world example.

8/26/20: See 2021 pricing update below.

I've written several times before about how health insurance risk pools work. I even whipped up a crude video explainer about them a couple of years back. The healthiness or lack thereof of a given risk pool is the biggest factor involved in determining how expensive or inexpensive insurance policy premiums will be.

This year, my own family became a perfect example of this. Unlike most health insurance horror stories you often hear about, the final results in our case are positive...although we did go through a brief panic attack period before getting there.

My wife and I are both self-employed, and have a few recurring medical issues. We have one child, a teenager with Asperger's syndrome and a (fortunately fairly mild) case of cerebral palsy, which means long-term physical therapy and some other recurring medical expenses. Since we'd max out the deductible on a Silver plan each year, we've been enrolled in an ACA exchange Gold HMO plan since 2015. It's expensive even with partial subsidies, but we don't want to risk a major hole in coverage if at all possible.

This is the major problem with many so-called "short-term plans", "association plans", "sharing ministries", "farm bureau plans" and other types of non-ACA compliant policies: They're dramatically less expensive on the surface...but generally achieve that by having massive coverage gaps, hidden costs and/or by simply cherry-picking enrollees via medical underwriting. While not all of them are "junk plans", the moniker fits in many cases.

This year, however, we found an option which, for us, resolves the cost issue without having to enroll in a "junk plan".

My wife is making a major career change, and has gone back to school to get her master's degree. The university offers student healthcare plans, of course, and they're available to the student's family as well.

Under the ACA, student plans offered at universities are regulated mostly the same way as other Individual/Family plans...but with a few differences due to the unique "neither fish nor fowl" status they hold. As Louise Norris explains:

Under the ACA, fully-insured student health policies (ie, non-self-insured plans) are considered individual market coverage, although they aren’t subject to the ACA’s single risk pool provision (ie, insurers have to put all of their ACA-compliant individual market plans together in one risk pool — including on and off-exchange plans — but if that insurer has student health plans available via a university in the state, they don’t have to put the student plan in the same risk pool as the individual market plans), and they also aren’t subject to the same guaranteed-issue requirements that apply to the rest of the individual market, since student plans are not available to people who aren’t students (or dependents of students) at a university that offers the plan.

But until 2018, student health plans were subject to the same rate review process as other individual market plans. As of July 2018, however, student health insurance is exempt from the federal rate review requirements that apply to other individual market plans. In finalizing this rule, HHS noted that universities tend to be savvy purchasers with considerable leverage — more like large employers than individual market consumers.

The second and third difference (the guaranteed issue only applies to students/dependents for obvious reasons, and the exemption from federal rate review) aren't that relevant here, but the first one absolutely is. I'll get to that in a moment, but first I wanted to briefly address the "panic attack" I mentioned above.

When we switched over from the ACA exchange plan to the student plan, it was done with the same insurance carrier, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, which should have made for a seamless, no-fuss transition. We enrolled well before the December 15th Open Enrollment Period deadline, made our January premium payment, and as soon as we received our new insurance cards from Blue Care Network, we thought all was well.

Unfortunately, my wife came down with a nasty cold/flu/bronchial thing over the holidays, went to the doctor just before New Year's and had to have a prescription filled on New Year's Day...the first day under the new policy. Immediately there was a problem: The pharmacy claimed that she wasn't insured and wouldn't cover the prescription.

Sure enough, when she logged into the Blue Cross account, our entire past history was there...but all three of us were showing up as no longer being covered as of 1/1/20. Ut-oh.

After going through some Hold Music Hell, my wife discovered that Blue Cross had initially entered the new plan into the system...but now claimed that they had never received the January premium, even though it had cleared the bank weeks earlier. Hoo boy.

Before I go any further, I should note that at this point our story didn't turn into a never-ending, domino-effect Kafkaesque nightmare, with one screwup leading to another. Instead, in our case, we were able to nip that in the bud thanks to some quick intervention from Blue Cross.

The university doesn't handle health plan enrollments directly...they contract out to a third party agency to do so, and that's who we actually pay our premiums to. They confirmed that they had received the payment and insisted that they had paid Blue Cross in turn. So what happened?

Several phone calls later, it turned out that our payment had been made...to the wrong policy account. Not to someone else's account--it was still in our name--but to our old policy.

So why didn't it show up under our 2019 Individual Market HMO account? Because of one other difference I didn't mention above--the new student policy is actually a PPO, not an HMO, and PPOs are handled by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, not Blue Care Network. Even though the two are owned by the same parent company, they're still two separate entities...and I had completely forgotten that we were enrolled in a Gold PPO for the first year of the ACA exchanges way back in 2014.

Apparently BCBSM attached our University Plan Gold PPO premium payment for 2020 to our long-defunct Individual Market Gold PPO policy account from 2014. This is why it didn't show up under either our 2019 HMO account via Blue Care Network or the 2020 PPO account via BCBSM.

This issue was straightened out within a day or two...but it led to a second problem: My wife was listed...but neither my son nor I were. Ut-oh.

A few more phone calls later, it look like the third-party administrator (TPA) misentered our last names. You see, my wife is the primary policyholder since she's the student...and she kept her maiden name when we got married, while our son has my last name. Thus, instead of "Gaba", both of us were entered with her last name...an interesting reversal of the headache that I'm sure millions of married women who keep their maiden name go through every day.

Once this was straightened out, voila: We're pretty much squared away, with all three of us listed on the proper account, with the proper insurer, enrolled in the proper student policy, with the proper last names. The only issue left is that several of my wife's pre-authorized prescriptions have been wiped out of the database, so she has to have those re-approved, although that shouldn't be a major issue (we hope).

Anyway, while some of this was BCBSM/BCN's fault, not all of it was, and they did resolve it pretty quickly, so this is among the rare times that you'll hear a health insurance carrier given praise for customer service.

With that out of the way, let's get back to my original point: Risk pools.

Before considering whether to switch from our ACA exchange plan or not, we first had to make sure that the coverage would be comparable; they were. We then had to make sure our doctors, hospitals and prescriptions are still in network; they are. None of this surprised us since both plans are via BCBSM, which also holds over 62% of the individual market in Michigan.

It therefore came down to price...and that's where I was afraid we'd have to make a judgment call, since there's a huge difference between the subsidized and unsubsidized prices of ACA exchange policies, and we never know from year to year whether or not we'll qualify for them.

My wife and I, you see, are a perfect example of the Subsidy Cliff® problem of the ACA. Not only does our annual household income vary greatly from year to year, at it's highest point it nudges just over the 400% FPL threshold. That means if we have an unusually good year, we actually lose nearly $4,400 in APTC tax credits. Ouch.

The Federal Poverty Line for a family of 3 is $21,330 in 2020. If we earn, say, 300% FPL (around $65,000), we're eligible for $531/month in subsidies (nearly $6,400 total). If we have a really good year and earn exactly $85,320, we receive $365/mo ($4,380 total). If we earn even one dollar more, however, we're eligible for nothing, and have to pay back the full $4,380 when we file our taxes the following year.

That's right: Thanks to the #SubsidyCliff, earning $1 more could cost us $4,380.

Here's how much the ACA exchange Individual Market BCN Gold HMO would have cost us in 2020 had we stuck with it, at full price as well as at various income levels:

At $86,000/year, (403% FPL) the premiums alone would be a whopping $17,400, or over 20% of our household income. at $85,000 (398% FPL), the premiums total $13,000...$4,400 less. This is the very definition of the #SubsidyCliff.

At $75,000 (352% FPL), it's an even $1,000/month; at $65,000 (305% FPL), it's $919/month, or around 16-17% of income, which is still absurdly high but at least starting to come into focus.

Before I compare it to the university-provided plan, however, I have to make an adjustment, because the student plan is a PPO, not an HMO...and PPOs cost more (we didn't choose to switch back to a PPO...it's the only plan available through the university).

Here's the equivalent BCBSM Gold PPO policy available on the ACA exchange in 2020:

YIKES. You can see why we had to abandon this years ago, even when the premiums were considerably lower for both PPOs and HMOs. At full price, this policy could cost as much as 29% of our income...an batshit $25,000/year for three people. Even at 300% FPL we'd still be looking at paying $1,560/month...that's over $100 more than the full price of the Gold HMO.

OK, so just how much does the university/student plan cost for a family of three?

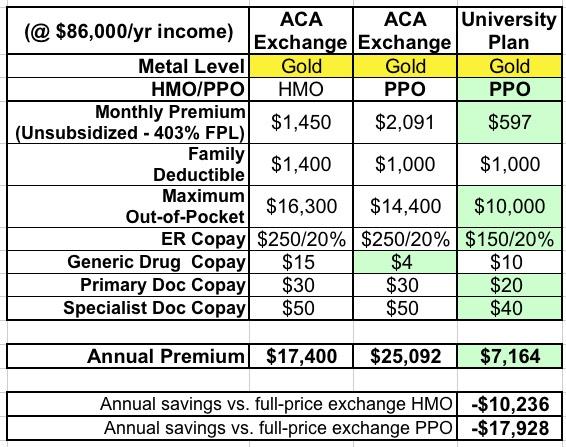

Remember, this is an ACA-compliant, Gold PPO from the same carrier, with the same network, the same drug formularly, required to cover the same services at the same levels as the individual market Gold PPO from the same carrier.

- $597/month

Yes, that's right: For all three of us, it amounts to $200/apiece per month. I was absolutely flabbergasted when I learned this.

Furthermore, the deducible is the same as the PPO (and less than the HMO) and the Maximum Out-of-Pocket total is much lower than either one ($10,000 for in-network care instead of $14,400 or $16,300 respectively). The co-pays are even slightly lower overall as well.

Here's how all three plans stack up on the major provisions at full price. The difference is staggering:

That's over $10,000/year less than the HMO and nearly $18,000/year less than the equivalent PPO from the exact same carrier.

Hell, even if you subtract my wife's tuition, we'd still come out ahead by a couple grand if we had to pay full price for the exchange version.

If our income for the year is low enough to qualify us for subsidies if we had stuck with the exchang plan, it's a different story...but even at 300% FPL, the student plan would still cost $3,800 less than the HMO and over $11,000 less than the PPO.

That's mind-blowing.

So why is there such a massive difference?

Well, I'm sure the university has a killer negotiating team, and perhaps there's some other deals which have been made which I'm unaware of--cross-promotional marketing or whatever? However, the most significant difference is the makeup of the risk pool.

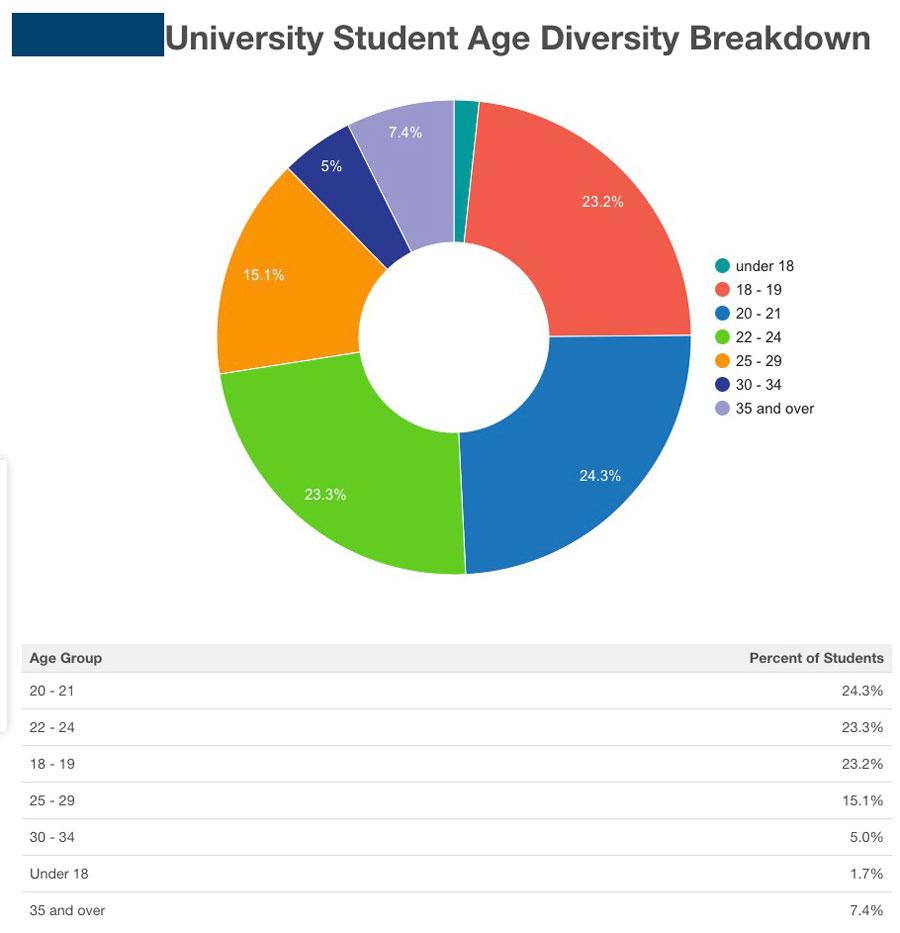

Here's an age group demographic breakout of the entire student body of the university in question (I'm keeping the name out of it for my wife's privacy). They have nearly 20,000 students total...which is actually higher than the total number of people enrolled in ACA market plans in Alaska.

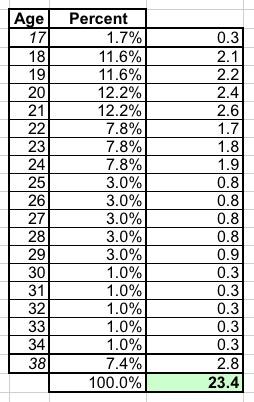

This particular university tends to have a higher portion of graduate students than most, so the average student age is a bit higher than the "18 - 22" you would expect...but not by much. A rough breakout (assuming "under 18" are virtually all 17-year olds and "35 and over" averages around 38 years old) puts the average at around 23 years old:

Of course, not every student is actually enrolled in a student health insurance policy...many are likely enrolled in their parents plan thanks to the ACA's "under 26" provision. At the same time, those who are enrolled (who are probably a bit older than the overall average) are much more likely to be married and/or have young children...and a 30-year old grad student who has a 30-year old spouse might also have a 5-year old child or two, let's say, which would more than cancel that out.

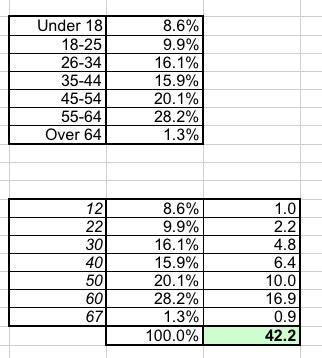

Now compare that to the average age of ACA exchange enrollees. They don't break it out by exact age, but I've taken the midpoint of each bracket and used my best guess for "under 18" and "over 64" to get an average of around 42 years old.

OK, so why is this a big deal?

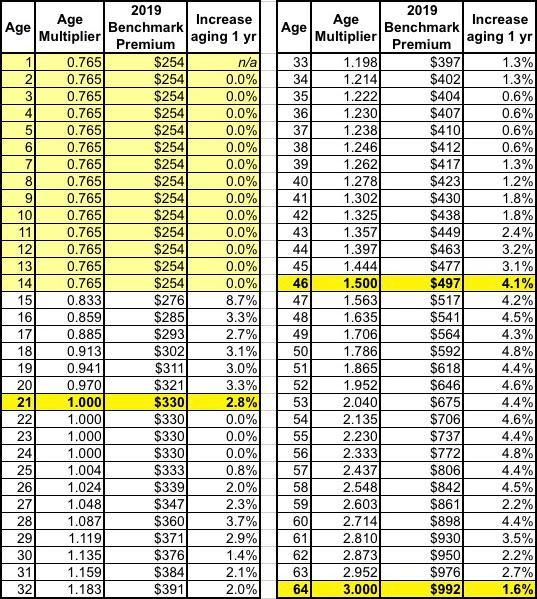

Well, here's the 3:1 Age Band used for ACA individual market premium rate settings:

At first glance, this makes it look like the average student plan enrollee (23 years old?) should have premiums around 25% lower than the average ACA exchange enrollee (42 years old). If so, that would mean our new plan would still cost over $1,500/month, not $597. What gives?

Well, here's a little secret about that 3:1 age band restriction: It's still not even close to being "actuarially accurate" in terms of how expensive the average older person is vs. the average younger person.

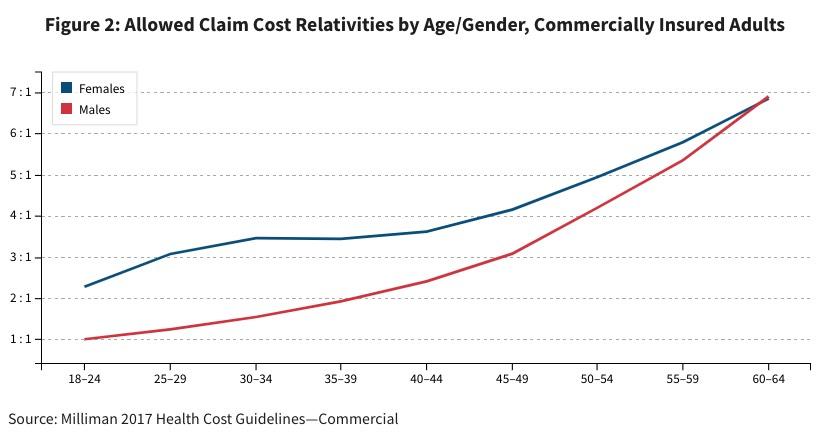

For that, let's take a look at this analysis by Doug Norris, Hans Leida, Erica Rode and Travis Gray in The Actuary Magazine:

In total, adult females incur approximately 33 percent more in total health care costs than their adult male counterparts. This difference is exaggerated at younger age levels, and is not entirely accounted for by maternity costs. Indeed, only 6 percent of adult female medical costs are from direct maternity care. Overall, if we were to apply a pure actuarial ratio to account for underlying health care cost differences in age and gender, we would expect to see a difference of approximately 6.9:1 between the highest-cost age/gender category (older men and women) in the commercial market and the lowest (younger men). These ratios represent allowed cost differentials, and as noted previously, the ratios would increase as the actuarial value of the plan decreased (going from platinum to bronze, for instance).

If one were to mandate unisex rates, as is done in the ACA rating rules (where males and females of a given age are charged identically), the variation by demographic cell is smaller, as the lowest-cost cohort (males age 18 to 24) and the highest-cost cohort (males age 60 to 64) are each blended with their female counterparts. Combining male and female data by age cohort, we find from the Health Cost Guidelines that the ratio of average allowed claim costs between the highest and lowest cells would be approximately 4.2:1.

Let me repeat that: If you strip away all legislative, economic, cultural, societal and other factors, from a pure actuarial perspective, the average 64 year old racks up 4.2 as much in healthcare expenses than the average 18-year old.

In reality, the average 42-year old doesn't just cost 33% more than a 23-year old...they cost more like 90% more.

This still doesn't explain the massive gap between the ACA Gold PPO and Student Gold PPO, however, where the ACA plan is more like 250% more. Even using the actuarial table above would still put the student plan at more like $1,100/month, not $597 (or conversely, it would put the ACA policy at just $1,134/mo).

So what else is going on?

Well, as David Anderson pointed out to me, there's some other important demographic differences here...some of which are depressing to think about, but again, we're looking at this from a callous actuarial perspective:

- University students are more likely to be of higher-income backgrounds...either upper-class or upper-middle class...and wealthier people tend to also be healthier on average;

- University student women may be less likely to become pregnant than other women of the same age; and finally, and perhaps most importantly...

- A student who develops a serious illness--especially one requiring long-term treatment--is a lot more likely to drop out of school for at least a semester and possibly a year or longer.

For that matter, even if the student themselves doesn't develop the illness, if one of their family members does, the student is still more likely to drop out for awhile, either to take care of their loved one or to get a job (or a second job) to pay the bills which mount up while the other family member is off work themselves getting treated.

Student plans understandably require the student to stay enrolled for at least a semester or two per year to remain eligible for the policy, just as employer plans require you to stay employed (COBRA notwithstanding). So if a student drops out, they're off the plan...along with their other family members.

When you take these factors into account, it becomes easy to see what's going on. Again, here's the distribution of total healthcare spending across the entire U.S. population:

As you can see, just 1% of the population racks up a whopping 22% of all healthcare spending nationally. 5% of the population eats up fully 50% of all spending, and 50% of the population is responsible for 97% of it. This means the remaining 50%--fully half the entire population--only imposes 3% of all healthcare spending nationally.

Once you realize which category the vast majority of college students fall into, and compare that against the average individual market enrollee, and you begin to understand how there can be such a chasm between the cost of two essentially identical healthcare policies. You can also easily see why attracting those so-called "Young Invincibles" into enrolling in ACA exchange plans is so vitally important.

UPDATE 8/26/20: We just re-enrolled in her university plan for the 2020-2021 school year (which will likely be all online/virtual, of course, given the COVID-19 pandemic), so I figured I should post an update on the pricing.

First, here's what it was for 2020 (from above):

For 2021, our University Plan premiums increased to $684/month, roughly a 14.6% increase, which isn't anything to sneeze at...but it's still a hell of a lot cheaper than the individual market plans we used to be enrolled in. I had to guess on the ACA exchange plans since the final rate changes for those policies haven't been approved as of this writing (they don't start until January 1st), but at the moment it looks like both BCBSM (PPO) and Blue Care Network (HMO) are only raising their premiums around 1.5 - 2.5% on average. Assuming deductibles, co-pays and other out-of-pocket expenses stay the same, that would give something like this:

- Unsubsidized ACA Exchange Gold HMO (BCN): $1,486/month

- Unsubsidized ADA Exchange Gold PPO (BCBSM): $2,127/month

- University Plan Gold PPO: $684/month

That's still a savings of $802/month ($9,624/year) or $1,443/month ($17,316/year) depending on which plan you're comparing it to.

My wife's full-year tuition, not including the healthcare premiums? $8,208. Assuming our income comes in over 400% FPL this year, we'd come out either $1,400 or $9,100 ahead by having her enrolled for the year.

Someone cited this article in their own blog (thanks to Aleka Gurel for the tip), and in doing so also pointed out another website which has taken this key point to the next level:

In fact…this is such an insane loophole that someone actually built out a site that shows how many credits you have to take at a school to qualify for their health insurance plan. In many states, the cost of taking the class + health insurance costs is actually lower than monthly premiums for a plan within the state.

How dumb of a system do you have to have for this to be a viable workaround.

That site is simply called "Healthcare is Dumb."

How to support my healthcare wonkery:

1. Donate via ActBlue or PayPal

2. Subscribe via Substack.

3. Subscribe via Patreon.