UPDATE x3: UnitedHealthcare: Is loose SEP enforcement part of the problem?

Over at Inside Health Policy, Amy Lotven takes a deeper look at one part of last week's UnitedHealthcare announcement which slipped by a lot of people:

United Notes Customer Churn As It Mulls Exiting Exchanges

...United in a Thursday morning call said it is seeing a high number of people who are purchasing exchange plans, receiving services, and then dropping their policies. Aetna, which last month announced it would scale back its offerings in 2016, also recently said is has seen an increased number of enrollees coming in and out of the exchange, especially through the special enrollment periods.

...Aetna Chief Financial Officer Shawn Guertin made similar comments in a Nov. 10 investors meeting at Credit Suisse. The phenomena that really we're seeing now is a lot more people coming in and out of the system, and in particular people coming in during a Special Enrollment Period and then staying for only a few months and dropping, is really part of what's draining the system, Guertin said.

...Former Aetna CEO Ron Williams says it seems the myriad special enrollment periods resulted in coverage of people who more likely knew about their potential need for health care services. In order to curb that type of behavior, Williams suggests eliminating the SEPs, and potentially increasing the individual mandate penalties. “At the same time we must be certain these people are getting needed health care service, but that the health exchange members are not asked to fund this adverse selection through higher premiums,” Williams said.

As I just posted, Molina, at least, says that they aren't seeing the Special Enrollment "gaming the system" problems that United and Aetna are talking about, but it's still worth looking into this issue.

First of all, just how many people do enroll during the "off season"? Well, last year roughly 9.6 million people actually selected a private exchange policy by the end of the year: About 8 million during the official Open Enrollment period (10/1/13 - 4/15/14), of which around 7.1 million actually paid their first monthly premium and were actually enrolled in their policies, plus another 1.4 million who enrolled via Special Enrollment (out of 1.6 million who selected policies) during the off season between 4/16/14 - 11/15/14 (after 11/15, of course, it was generally too late to enroll for 2014 coverage, and 2015 Open Enrollment had begun).

1.4 million between mid-April and mid-November is around 6,500 people per day. At the same time, a similar number of people (or higher) were dropping their coverage every month throughout the year, resulting in only around 6.3 million still being enrolled by the end of December.

Now, it's important to note that there's nothing wrong with people dropping their coverage a few months after starting it...depending on the reason for the coverage being dropped. Of the 2.2 million people or so (give or take) paying enrollees who dropped their policies at some point throughout the year, many of them did so for completely legitimate reasons:

- They might have turned 65 and moved to Medicare.

- They might have lost their jobs and moved to Medicaid.

- They might have gotten a new job with Employer Sponsored Insurance (ESI).

- They might have gotten married to someone with ESI.

- They might have switched to some other form of coverage.

- They might have, well, died.

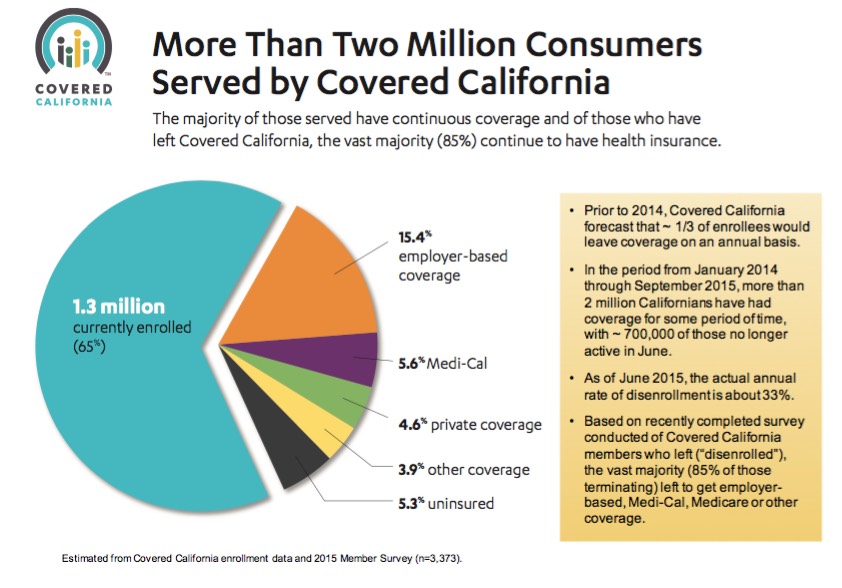

In any of those cases, none of the "gaming the system" concerns should apply; these are all reasonable cases for dropping your exchange coverage. While there's no national breakout of the reasons for people dropping out, Covered California has provided just that for the 2 million people who were enrolled in private policies at some point or another over the past 2 years:

According to this report, out of the 35% of at-one-time CoveredCA enrollees who have since dropped out (remember, this includes 2014 as well as the first three quarters of 2015), only 15% of them (5.3% of the 2 million total) are currently completely uninsured. The other 85% moved to some other form of coverage instead.

Of course, it's entirely possible that some of these folks were simply lying about why they dropped, but let's assume for the moment that this is accurate. Let's also assume, for the moment, that California's experience is representative nationally:

Assuming that California is representative nationally, this suggests that out of the roughly 16.4 million people (around9.6 million in 2014 and an additional 6.8 million thru 6/30 in 2015) who have selected private policies via the various ACA exchanges since October 2013, perhaps 870,000 are back to being uninsured now...but that's still 15.5 million who have full coverage of one sort or another. Not bad at all.

Of course, a large chunk of that 870,000 likely consists of the 535,000-plus people who were kicked off of their policies involuntarily due to being unable to resolve legal residency issues (112K in September 2014, 423,000 more as of June 30 of this year).

So the real question here is: How many of those 870,000 or so people deliberately took advantage of the Special Enrollment Period allowances ("Qualifying Life Events") to enroll in a policy short-term just so they could have a specific, expensive medical issue treated/operated on/whatever, and then dropped their coverage as soon as they were healed?

This is called "gaming the system", and it's exactly the reason for having a limited-time Open Enrollment Period in the first place: To prevent otherwise healthy people from waiting until they're diagnosed with cancer/diabetes/lyme disease/gout/whatever to sign up (in order to avoid having to pay the premiums) and then signing up, getting a few months worth of expensive medical care and then dropping the coverage like Kryptonite after that. If too many people do this, they can rack up millions of dollars in healthcare claims while only paying a few months' worth of premiums, jacking up costs for everyone else. Obviously this sort of gimmick makes less sense for some ailments (cancer) than others (a broken leg), but you get the picture.

The whole point of a 3-month open enrollment period is to basically play chicken with your health (or Russian Roulette, perhaps? Pick your metaphor). In general, you have 3 months out of every 12 month year to sign up for health insurance coverage. If you miss that 3-month window, you're out of luck until the next Open Enrollment Period.

A Healthy Person® who doesn't sign up during Open Enrollment is basically taking a gamble: They're betting that they won't become seriously sick or injured over the next 9 10* months. I'm not sure how this translates in "odds" format, but I think it means they're betting that they have a 1 in 4 1 in 6 chance of "winning" vs. a 3 in 4 5 in 6 chance of "losing". Perhaps I have those odds backwards, but again, you get my point. Medicare itself, as well as most Employer Sponsored plans, have been using the "Open Enrollment" system for decades; this is nothing new or unusual.

UPDATE: Thanks to Michael Hiltzik for pointing out that it's actually 10 months, not 9; if you wait until 1/31 to make your decision, your coverage would start on 3/1/16, but coverage for the next enrollment period wouldn't start until 1/1/17, so that's 10 months, or 5 in 6 odds, not 3 in 4.

The Special Enrollment Periods (SEPs), however, throw a monkey wrench into this system.

The reason for SEPs is that people's personal situations are changing all the time. If someone doesn't sign up because they have coverage through their job, but then loses that job in March, it's pretty unreasonable to tell them they can't sign up until the following November. The same holds true with a woman giving birth; if she signs up for herself during open enrollment but doesn't give birth until June, she has a bit of a problem even if she's trying to comply with the law (you can't "enroll" a child who doesn't exist yet--they don't even have a Social Security number, for one thing!!), and so on.

As a result, the HHS Dept. has about a dozen "Qualifying Life Events" which allow people to enroll in exchange policies (or off-exchange, for that matter, I believe) at any time, regardless of whether it's during open enrollment or not. In most cases, you have up to 60 days after these events take place to sign up using a SEP exception:

- Having a baby, adopting a child, or placing a child in foster care.

- Marriage.

- Losing other health coverage.

- Moving to a new state.

- Changes in your income that affect the coverage you qualify for.

- Gaining membership in a federally recognized tribe or status as an Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) Corporation shareholder.

- Becoming a U.S. citizen.

- Leaving incarceration.

- Change of dependency status of someone on your plan.

- Death of a covered member of your household.

- Turning 26 and aging off your parent's plan.

- AmeriCorps VISTA members starting or ending their service.

In addition, of course, for 2015 in particular, every state except 3 allowed a one-time Tax Filing Season SEP as well for people who "didn't know" about the individual mandate tax penalty, etc, etc. Around 214,000 people nationally took advantage of this, although it's unlikely that this will be offered again in 2016.

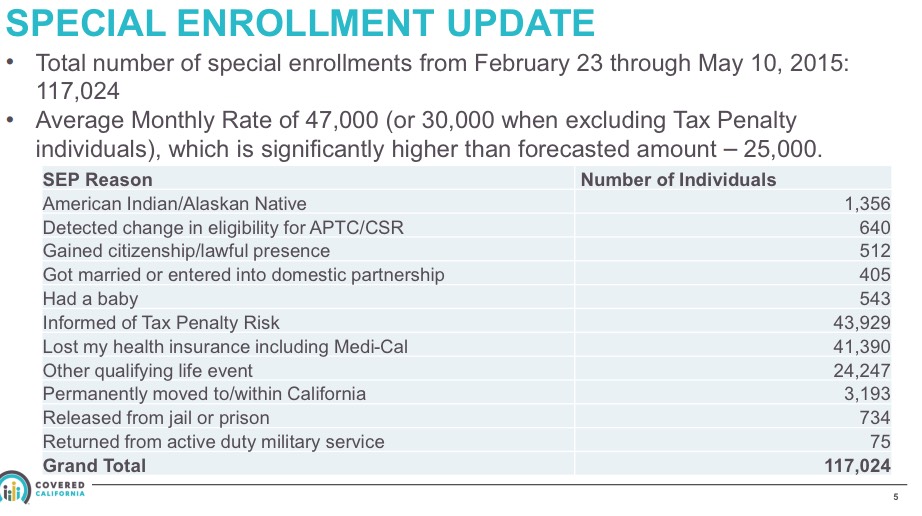

Some of these are pretty obscure, of course (AmeriCorps, getting out of jail, etc), but others are quite common. Here's how California's SEP numbers broke out as of late May:

As you can see, the vast majority of people joining the exchange claimed that this was due to either Tax Penalty Ignorance, losing their current coverage or "Other Qualifying Life Events", whatever those are.

I guess the question here is just how much verification the HHS Dept. and/or the assorted state-based exchanges are doing of these claims. In cases like getting married/divorced, giving birth, becoming a citizen or getting out of jail, I would imagine the verification should be pretty easy. However, the "Tax Penalty Ignorance" exception was pretty much based on an honors system, and I don't know how easy/difficult it is for the feds to "verify" that your income has increased/decreased substantially...at least, not until you file your taxes the following year, which could be up to a year after the claim is made.

In addition, those 535,000 people kicked off the exchanges for residency verification issues could also be a large part of the problem, since they're given 95 days to provide the appropriate documentation before being given the boot.

Finally, as ACA opponents Megan McArdle and Bob Laszewski noted a year ago, there's another big opening which people can take advantage of:

Under Obamacare, after a person has paid their first premium, a health plan can't cancel anyone until they have gone three months without making a payment.

Yup, the ACA does indeed include a 3-month "grace period" before enrollees can be kicked off:

The Affordable Care Act, and subsequent regulations released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), made numerous changes to the health insurance marketplace. One area of concern for family physicians is new regulations that extend the time that services are deemed covered in the event that a lapse in payment occurs. The ACA provision extends, to 90 days, the grace period in which patients have to “true up” any past payments prior to the insurance coverage being terminated.

Current laws [this was presumably posted prior to 2014] and regulations on late and outstanding premium payments vary by state, with some states allowing insurers to drop consumers’ policies without advance notice. Other states require insurers to offer a 30-day grace period before dropping customers’ plans. Under rules issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), consumers will get a 90-day grace period to pay their outstanding premiums before insurers are permitted to drop their coverage. The rule applies to all consumers, in all states, who purchase subsidized coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) health insurance marketplace.

The rule also requires insurers to reimburse providers during the first 30 days of the 90-day grace period. If a consumer still fails to make a payment after 90 days and his or her coverage is dropped, depending on most state laws, insurers will not be required to pay for claims incurred during the last 60 days of the grace period. If coverage is dropped for nonpayment, physicians must work directly with patients to collect payments for the balance incurred during days 31-90 of the grace period.

You can see the potential for mischief here, especially since the ACA's individual mandate rules also allows people to remain uncovered for up to 3 months without having to pay the individual mandate penalty.

In other words, theoretically, you could go without being covered for January and February, start your coverage on March 1st (you have to be covered for at least 1 day of the 3rd month), pay for March, April, May, June, July, August and September...but not bother paying for October, November or December.

If someone does this, they would be covered for 8 months of the year (and kind-of, sort-of covered for 2 more months), but would only pay for 7 months of premiums...all without having to pay the individual mandate penalty.

Result? The insurance carrier provides 8 months worth of services for 7 months of premiums, and may/may not end up getting into legal headaches with their provider network over another 2 months worth of services.

So, what's the solution to this, assuming the problem is widespread? Well, I can think of some obvious tweaks to the rules, almost all of which involve simply reducing grace periods:

- Shorten the 90-day Payment grace period down to 30 or 60 days.

- Shorten the 95-day Residency Documentation data matching grace period down to 30 or 60 days.

- Shorten the 3-month Individual Mandate grace period to 1 or 2 months.

- Shorten the 60-day grace periods for having a baby, getting married, etc. down to 30 days.

Beyond that, I'd imagine it's just a matter of tightening up the verification of any/all of the above, assuming that it's not being checked very thoroughly at the moment.

UPDATE: Thanks to FarmBellPSU in the comments for this link to an interesting White Paper on 2016 rates in Iowa from Wellmark; this snippet from the third page is key:

There were 135 members who signed up for coverage, received several million dollars in health care services, and then terminated their coverage. Wellmark received only approximately 10 percent in premiums to cover those members’ health care claims.

They don't go into specifics, but let's assume these 135 people collectively racked up $2,000,000 in services, while paying an average of $500/month per enrollee, but only stuck around for 3 months on average. That'd mean $202,500 in premiums being paid out for $2 million in claims.

The same White Paper says that Wellmark has roughly 30,000 exchange enrollees in Iowa, so that's 0.45% of their enrollees allegedly gaming the system by a large amount. I have no idea whether this is accurate or not, or if it is, whether it's representative among other carriers state-wide or nationally, but let's assume it is.

If so, that would mean roughly 45,000 people racking up 10x their premium rates in expenses by gaming the system for a few months. Assuming, again, an average of $500/month premiums and a 3-month stay for each, that's $67.5 million in premiums paid for a whopping $675 million in services rendered...or over $600 million in losses nationally.

In addition, a large number of members purchased a premium-level plan in anticipation of using a large amount of services, knowing that they would later qualify for a special enrollment period that would allow them to move to a lower cost plan.

Now this is an angle I hadn't considered. Here's how I presume this would work:

- Let's say it's early December, and you're getting married next March.

- You enroll in a Platinum plan (zero deductible, 90% coverage) for $1,000/month

- You quickly arrange for a whole mess of services (I dunno...taking care of that pesky gangrene problem by having a leg amputated?) in January and February, paying $2,000 in premiums for the first two months

- When you recover in late February, you'd normally be stuck with the Platinum policy for the rest of the year, costing you a minimum of $10,000 more

- However, once you get married in March, you qualify for a Special Enrollment Period which allows you to switch your coverage to a dirt-cheap Bronze plan for just $100/month. It has a $10,000 deductible but hey, your gangrene-infected leg is already gone, so you're (theoretically) cool.

- Result? You end up paying just $3,000 total in premiums for the year ($1,000 x 2 months + $100 x 10 months) instead of $12,000.

Of course, this assumes no other expenses, injuries, ailments, etc. throughout the course of the year, but you get the point. Note that this scenario assumes that you actually have ACA-compliant coverage for the full 12-month period and don't take advantage of any of the grace periods. Doing so could theoretically let you get away with stiffing the carriers for 2-3 more months of coverage on top of that.

Don't get me wrong, I'm not crying in my beer over the poor insurance industry (when they stop paying their CEOs $10 million/year apiece, I'll be more sympathetic), but this is a legitimate problem which needs to be addressed.

UPDATE x2: Louise Norris has clarified a few things about the "Grace Period" issue for me (these are via Twitter, so the wording is a bit cropped):

- The penalty exemption is for less than three months (ie, 3 months = penalty), and only the 1st short gap in the year counts.

- So a person who is uninsured Jan, Feb, Oct, Nov, Dec would be penalized - only the first short gap (2 months) would be exempt.

OK, so that's a little better on the penalty exemption front. As for how difficult/easy it would be to reduce that grace period, it looks like it'd require Congressional action after all (also from Norris):

- ACA says 3 month grace period required for enrollees receiving subsidies.

- Related: gap that spans 2 years will result in penalty, even if only 2 months in each year.

Finally, Hans Leida of Milliman (one of the top actuarial firms in the country) posted a much more in-depth look at the "90-day grace period" issue last year which gives more detail than you'd ever want about this subject.

After all of the above, I guess my real question is this: DOES CMS/Healthcare.Gov actually verify SEP eligibility at all? I've never needed to use one, so I don't know what happens when you try to do so. Does it require you to upload a copy of your marriage certificate, the birth certificate for your newborn, a termination notice, change of address form, etc etc? I have no idea. How about the state-based exchanges?

I don't imagine that there would be any way of proving fraud for dropping your coverage at any time after signing up as long as you've paid the minimum number of monthly premiums, but signing up during the off season should have some sort of verification process.

UPDATE x3: Hmmmm...interesting. A guy in the comments says that on the Massachusetts exchange, at least, he had the opposite problem when his daughter was born:

Yes, I have an exchange plan, and my daughter was born in March. It took 3 months of hour-long phone calls, about 50 pieces of documentation, and the intervention of my state representatives to get her added to my plan, so if anything, they overenforce the SEP - a birth certificate should have been sufficient.

This doesn't really address the HealthCare.Gov situation, of course, as every exchange has different procedures for the enrollment process, but it's worth noting that at least one state exchange is being (overly?) zealous on SEP verification. Of course, Massachusetts has had an ACA-like system for a lot longer than the other states (Romneycare, anyone?), so they're presumably more experienced at this sort of thing...

How to support my healthcare wonkery:

1. Donate via ActBlue or PayPal

2. Subscribe via Substack.

3. Subscribe via Patreon.